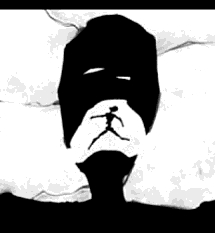

Killing Monsters: Why Children Need Fantasy, Super Heroes, and Make-Believe Violence

Killing Monsters: Why Children Need Fantasy, Super Heroes, and Make-Believe Violence by Gerard Jones. Basic Books, 2002, 261 pages, $15 US.

by Gerard Jones. Basic Books, 2002, 261 pages, $15 US.

Brief overview of content:

Gerard Jones writes about the significance and the value of fantasy violence for children, whether they are five or twenty-five. In addition to participating in the comic book and fantasy industry, he also runs workshops at schools where students tell stories in verbal or visual formats. He discusses their works as art and as an expression of what they think and how they feel about what's important to them. He has also read extensively and interviewed many professionals and authorities in the field of children's entertainment and development. The book that emerges from all of this looks at fantasy violence from many different angles and perspectives.He discusses what children really seek in fantasy superheroes and pop culture: being strong and discovering who you are. He engages in the many venerable studies that link entertainment violence with increased aggression, debunking the results with very convincing arguments. He analyzes children's interest in toy guns as a manifestation of the cross-cultural desire to have a tool to fight something greater than themselves (like a spear or bow and arrow to fight animals in some cultures or magic wands in most cultures). He examines how the role of women in fantasy has changed dramatically, from being objects of desire and/or protection to being heroes in their own right. Throughout the book he discusses the line between fantasy and reality, especially how this is blurred by the desire of modern media (both entertainment and news/information) for sensationalism (which began in the 1800s!). He provides parents with various ways to help their children in dealing with real and fantasy violence by modelling (showing how you react as a thoughtful adult), mirroring (affirming who they are and what they desire and how they use story-telling and play to process their experiences and feelings), and mentoring (helping children take control and allow them their reactions, intervening when necessary and with care). Finally, the most important thing is for parents to be involved in a conscious and conscientious way with their children, talking to them about their fears, their desires, what they did that day, everything.

Copious notes for each chapter are found at the end of the book as well as a thorough index.

Author overview:

Blurb from the back of the book: "Gerard Jones's previous books include Honey I'm Home: Sitcoms Selling the American Dream and The Comic Book Heroes. His work has appeared in Harper's, The New York Times, and other publications. He is also a former comic-book and screen writer whose credits include Batman, Spider-Man, and Pokemon, and whose own creations have been turned into video games and cartoon series. More recently he has developed the Art & Story Workshops for children and adolescents. Jones is the founder of Media Power for Children and serves on the advisory board of the Comparative Media Studies Program at M.I.T. He lives in San Francisco with his wife and son."Recommendations:

1. Read cover to cover vs. consult as needed.

The book doesn't really deal with specific issues like, "what do I do if my child is addicted to Pokemon?" so it isn't going to provide solutions. It is fascinating throughout and I recommend going cover to cover. It is longer than most books I've read for this blog and did take me a while to get through it. The book is totally worth the investment of time.2. Readability.

The prose is easy to read. He makes his points with arguments and examples from his research and experience with children. He definitely employs the art of storytelling to advance his thesis which makes him more engaging.3. Helpful to a parent?

Reading this book makes a father or mother engage in a more in-depth way with issues around fantasy violence and its effects on children of all ages. As long as you come to it with an open mind, the experience will be very rewarding, even if you don't agree with the author.4. Did we use it?

This isn't the sort of practical book for specific actions. It's more for general awareness of issues around fantasy violence, toys, and play, encouraging parents to be more open to how the children truly value them. Often, people have the knee-jerk reaction that violence is bad and my child should not be into that kind of stuff. I plan to make my wife read it so we can discuss it. Hopefully we'll be done in time to buy appropriate Christmas presents for the children!Sample text

For a lot of young people, unfortunately, the wall between the fantasies they crave and the world they're asked to participate in has been raised too high. One of the forces that's built that wall has been our efforts to banish aggression and violence. We draw such a sharp ideological and social line between what's "good for us" and what's "junk" dealing with make-believe power and violence that some kids feel that they're in an either-or conflict. They don't have cues to show them how to build from their power fantasies and become more powerful in reality, and they feel that the world of fantasy entertainment is the only place that is safe and welcoming.That line is reinforced within the media itself, where "educational" and "commercial" producers have drawn into two warring camps. Anna Home, OBE, the head of children's television for the BBC during its most adventurous years, has described the art of programming as "walking a tightrope between what children want to see and what adults think they should see. If one errs, it's far better to err on the side of what the children want. Unfortunately, the powers that be rarely let one do so." Attempts to integrate the two can produce good results, but they tend to founder when physical conflict enters the picture. The Fox network once tried to fill the "educational" portion of its programming with an intelligent action cartoon, Sherlock Holmes in the 21st Century. It was a smart show, produced by very conscientious creators at Dic Entertainment. Two children's media authorities, Drs. Donald Roberts and Dona Mitroff, made sure that every action scene demonstrated the superiority of brains to brawn, showed the hero turning his opponents' force back at them, and never depicted serious injury or death. But when the episodes were reviewed by the Annenberg Foundation, which advises producers and the FCC on educational content, every pratfall by a villain, every exploding evil machine, every deft judo throw, was blasted in the report as "violence." The show did reach the air, in a somewhat different form and with different people attached, but an opportunity for a major research foundation to reconsider what "violence" might be, an opportunity to bring the "official" version of what's good for kids together with what kids really like, was lost. [pp. 224-225]